Towards a Planetary Theology

Every political innovation requires, first of all, a corresponding transformation in the cosmos. To remake globalization from a gangster racket into a genuine political society, we must recognize theology’s foundational role in shaping political order.

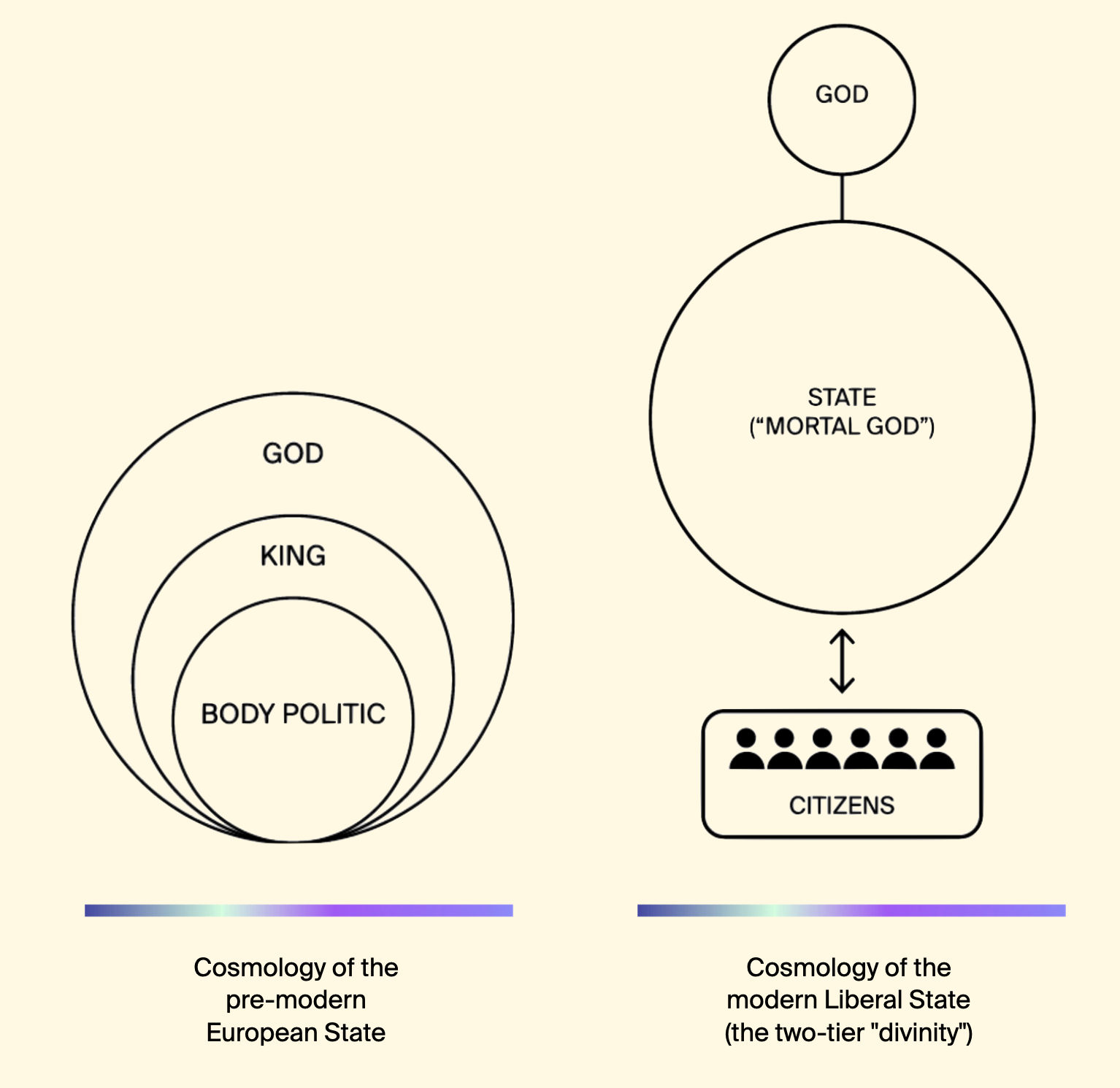

Most of the “philosophers” of the European Enlightenment were, before anything else, theologians. The crisis they sought to resolve, equally, was theological: since Europe’s principalities drew their authority from God, they were fatally vulnerable to religious heterodoxy—which was proliferating at that time and tearing them apart. The philosophers’ response? Push God into the remote universe and transfer his divine attributes to a new, proximate godhead: the state. Miracles were excluded, for instance, as a first principle of modern sovereignty: the state was absolute and would not endure interventions by a higher power. The most striking novelty of what Hobbes called the “mortal God,” however, was this: the state was supplied with authority, not from above, but from below—from a parallel innovation, the national people.

Three observations are necessary to our discussion here. First: the new—“secular”—state was not empty of religion. No functioning state, in fact, could—or can—be so empty. Rather, it was inflated by a new faith: a reformed version of Christianity we can call, for the sake of simplicity, “liberalism”—which transposed the “Kingdom of Heaven” to the nation, whose inexorable progress would bring about freedom, equality, and fraternity in the present life. Second: the modern state assumed not only the attributes of the Christian godhead—omniscience, omnipotence, all-goodness, etc—but also the associated passions. Nationalism was a religious force, and contests over the nature and purpose of the state were pursued with crusade-like intensity. Third: since the national people had become a sacred abstraction—usurping the place of divine authority—acute anxieties emerged regarding its scope and definition. Most insidious was the question of suspect insiders. The worst modern violence has been reserved for those deemed to have infiltrated and corrupted the national body.

In fact, political renewal is impossible if we do not first renew our theology: every political innovation requires, first of all, a corresponding transformation in the cosmos.

The eighteenth-century reorganization of religious forces saved the European state, laying down new and more robust theological foundations, which were eventually extended around the world. Today, however, those foundations are crumbling. This is the background to the crisis of faith evident in so many national discussions today—as well as the resurgence of beliefs and superstitions that, according to liberal notions of providence, should have died out long ago. Since Western political science has come to disdain theology, however, these unstopped genies are viewed as distractions from the main task—which is to preserve our political architecture from the assault of twenty-first-century forces. In fact, political renewal is impossible if we do not first renew our theology: every political innovation requires, first of all, a corresponding transformation in the cosmos. It is important we trace the historical arc of liberal monotheism, therefore, so we may know what, in theological terms, we have to work with.

At the time liberalism was formulated, there were no liberal states. Eighteenth-century states could not “afford” the political rights and privileges outlined by the philosophers. Liberalism was idealistic: it created needs and aspirations that could only be fulfilled by an as-yet-non-existent mode of industry and technology. Even in Europe’s national colonial states—which were able to use resources plundered from abroad to deliver political advancement at home—the process took at least 100 years. Between 1870 and 1970, however, the West’s high-industrial monopoly produced the conditions—rapid growth, near-full employment, a dynamic bureaucracy, a standard of living much higher than the rest of the world—for the covenant to be redeemed.

Those conditions did not exist outside the West, where the generalization of the nation-state form produced other theologies. Russia, a collapsed and uncompetitive empire, proposed a state blazing with its own non-derived authority, oriented towards a more distant but more complete salvation of the people. Terrifying levels of extraction were levied in the name of that hope, allowing the agrarian laggard to become a leading industrial power within a few decades. During the Cold War, the Soviet Union and the United States both tried to convert foreign nations to their distinct conceptions of the paradise to come. Around the world, political elites blended the two dominant orthodoxies with local cosmologies, creating their own gospels of national deliverance. In many poor countries, material improvement was projected far in the future, and these gospels were the only cohesion: great energies were often expended, therefore, on policing heresy.

Despite the divisions of the Cold War and the immense inequalities between nations, the post-1945 world was more homogeneous, in theological terms, than we tend to think. Liberalism and communism were sibling faiths, after all, born of an internecine schism—and they shared an unfolding sense of time. The cry of “Progress!” rang out everywhere: whether in Algeria or Poland, Japan or Argentina, governments promised a tomorrow better than today. There was endless debate, within and between nations, about how that could be achieved, but all parties measured success with the same, secular, indices: health, education, industrial capacity, economic growth, and the like.

Like any new monopoly, liberalism lost its radical impulse.

Globalization has brought an end to the theological uniformity of the “national” period. That may seem paradoxical, but it is not. Global integration undermined the proud religions on which that uniformity was based; since then, states have had to shore up their authority with local improvisations—diverging significantly, in the process, from each other.

The undermining processes are well known. In leading Western states, the delicate moral contracts that had arisen since the 1940s between national capital and labor were curtailed; corporations moved jobs to where no such contracts existed—and what would hitherto have been called illegality now became the driving political purpose. All over the world, globalization produced systems—SEZs, offshore havens, informal corporations, finance, crime, and terror networks—designed to outflank national regimes of law, tax, and “progress.” The collapse of the Soviet Bloc hastened this corruption of the liberal promise: like any new monopoly, liberalism lost its radical impulse and mutated instead into elite self-justification. The language of “rights” was turned against its ostensible—humanitarian—purpose: now it became a vehicle for privatizing the social surplus. Everywhere, states cannibalised previous advances of the “national people” the better to compete for capital—and the old progressive gospels collapsed into implausibility.

Theological chaos is most acute, perhaps, in the West, where states have not only withdrawn from the covenants of the high era, but also ceded key areas of their own authority to private finance and technology, and lost their decisive advantage over the rest of the world. Especially over China, whose destruction was necessary for Western liberalism to succeed in the first place, and whose return confronts it once again with that alien, dynamic cosmology that subordinated Europe’s for so many centuries. The “mortal God” is fading, and there is a sense of what one writer called—in the midst of a previous European crisis—a “dusk of nations, in which all suns and all stars are gradually waning, and mankind with all its institutions and creations is perishing in the midst of a dying world.”

The dusk abounds with anti-orthodox sects and cults, superstitions, and blasphemies. The beliefs, for instance, of those we might call “Old Believers”—who seek to retrieve the radiance of some far-off, unfallen time. Viktor Orbán is the most articulate representative of this attitude, which fuels the upsurge in “right-wing populism” across the West. Some Old Believers would go so far as to undo eighteenth-century innovations—calling God back, for instance, from his exile, introducing miracles back into state life, and re-opening the passage between terrestrial and celestial realms. But the main obsession is treachery from the outside. Feeling that the national people is thoroughly compromised by internal enemies, Old Believers seek to restore some uncorrupted form of sovereignty. Pogroms are a real threat. Democracy itself might be in question: the national people is full of foreigners and dissenters, and political authority might be more securely derived, once again, from above not below. The fixation on corruption produces policy proposals that run counter to technocratic success—preventing inflows of workers and ideas, purifying the territory of eccentric personalities, installing masculine leaders to re-domesticate human fertility, withdrawing from debilitating foreign obligations—but it was soulless technocracy, Old Believers might say, that got us here in the first place.

Another countervailing upsurge comes from “Puritans,” who are most numerous among students and the young; their spirit is captured, perhaps, by Greta Thunberg’s provocation to incumbent generations: “You have stolen my dreams and my childhood with your empty words.” In this view, corruption is not foreign: it comes from within. “We” are to blame—for our love of wealth and power and our eternal campaign against people and nature. The state is no sublime divinity; it is more like an occult ogre—and no deliverance is possible while its appetites and predations are not atoned. The museums must be emptied where the Bad Father has celebrated his legacy of fire and rape; institutions must be rebuilt from scratch. Every element of the patriarchal order must be dismantled, including God and nature, man and woman. The Puritan dream is innocence, which is animistic and remote, existing only outside categories and power systems: in trees, animals, and the unborn; non-state peoples; the pre-historic past.

The cosmological breakthrough we require is equivalent in scale to that produced by the Enlightenment itself, and it demands the attention of the world’s leading institutions and most talented thinkers.

There are parallel outbreaks elsewhere. National promises have been trampled in most places, but outside the West there is an additional alienation: perhaps those promises were foreign and misguided in the first place. Old Believers are especially common in states with grandiose traditions, where Western liberalism is re-cast as a neocolonial conspiracy aimed simply at maintaining the West’s monopoly over economic and political resources. Mocking its fraudulent claims to universalism and promising to restore their own nations’ spiritual glory, leaders like Putin and Modi present themselves as holy warriors against corrupt foreign religions. For Benjamin Netanyahu, liberal concepts such as “separation of powers” betray the sacred purpose of the Israeli state, which should not be limited by cynical controls. Israel’s military defense need not obey secular law, nor even any intuitive arithmetic of violence. Many other states are drawn to a similar logic: theocratic nationalism is proliferating once again, to the point that we risk the society of states returning to the terror from which it was born.

But we should not imagine the Puritan alternative is gentler. Amid the increasing polarisation of world affairs, in fact, the most common miscalculation is this: fearing one extreme, individuals and states underestimate the danger of the other. The most conspicuous Puritan response comes from radical Islamism, which has the potential seriously to erode accumulated political resources—and therefore security and peace. The most influential theologian of the last century is Sayyid Qutb, who argued that nation-states are contrary to divine law. Only Allah possesses legitimate political authority, which is universal; the “mortal God” of the state is a false idol, and national life is blasphemous. Many techniques have since been developed to clear the earth of these unholy structures; the most conspicuous is to “play” the blind militarism of nation-states themselves—to provoke, say, the United States with an intolerable terrorist affront, so it unleashes its own military fury on the nations.

Sayyid Qutb’s ideas have shaped the most extreme example of theological divergence among today’s states: the Islamic Republic of Iran. Self-evidently, the authority of this state is not based on the promise of secular “progress.” In fact, its ambition is anti-national—even anti-terrestrial—and requires immense repression of the domestic population. That ambition: sustaining the Islamic revolution until all nations are replaced by a world Islamic order—or what the constitution calls “universal government.” Possessing many of the attributes of a nation-state, the Islamic Republic is a paradoxical creation of the “global” era: it operates through non-state networks to undermine the nation-state system itself.

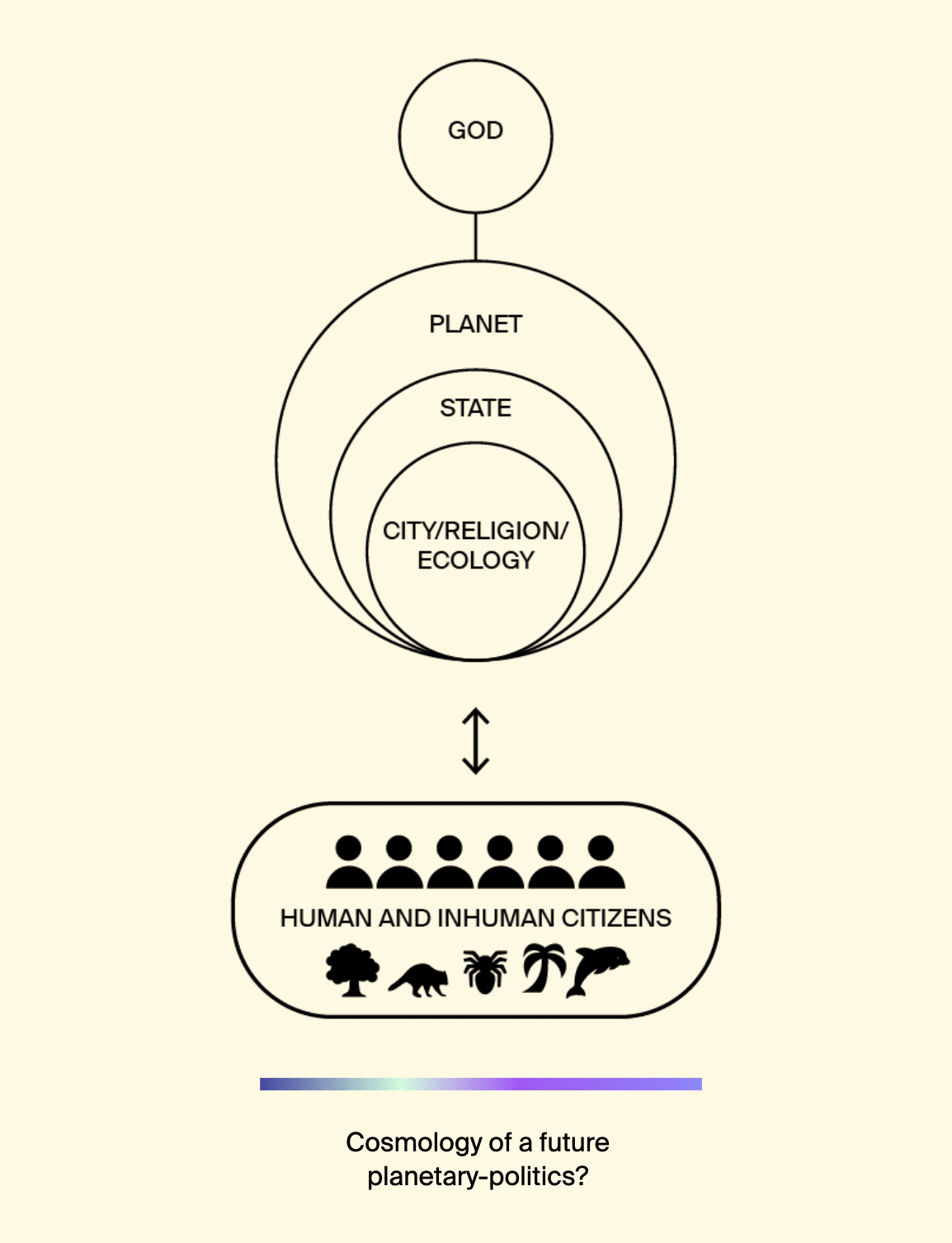

None of these flare-ups—Old Believer or Puritan, Western or non-Western—can supply a productive vision for political life in the twenty-first century. But nor can liberalism—at least in its present form. Old Believers and Puritans each express, in fact, a non-trivial dissatisfaction with liberal orthodoxy. Old Believers recognize that national sovereignty has been significantly weakened, leaving “the people” with little capacity to determine the distribution of resources. Puritans understand that gentler, loftier objectives are overridden by a heartless maelstrom of state competition, which robs us, also, of any aspiration towards the universal. One way to resolve all these positions is to imagine a planetary politics to supplement the present, national, form. The objective would be (1) to preserve the initial promise of liberalism—freedom, equality, and the rest—whilst (2) creating political capacities able to operate at the scale of “global” networks, licit and illicit—and so restoring lost sovereign powers, and (3) enabling a new, universal, account of social and economic objectives.

Just as then, we need extraordinary reformulations of the nature of God; drawing on all religions, theologians must again place distance between the planet and the godhead and find a way for earthly affairs to glow with their own divinity.

As we know by now, however, such a shift in political scale would first require a radical theological overhaul. This, I would argue, is the greatest intellectual task of our moment. Certainly, it is too important to be delegated to monomaniac priests and xenophobic “influencers.” Our shared future hangs on it, and it cannot be left to those who have nothing to lose. The cosmological breakthrough we require is equivalent in scale to that produced by the Enlightenment itself, and it demands the attention of the world’s leading institutions and most talented thinkers.

The project exceeds the scope of any one thinker, and I cannot anticipate it here. All I can offer are some disconnected notes.

This reformation should remain faithful to some core liberal concepts, whose merit has not diminished simply because they have been distorted and besmirched. Freedom, equality, fraternity: these are as radical and essential today as they were in 1750. Just as then, we need extraordinary reformulations of the nature of God; drawing on all religions, theologians must again place distance between the planet and the godhead and find a way for earthly affairs to glow with their own divinity. We need another account of time, which is secular but benign: material and moral progress must once again become plausible—as a collective terrestrial project, not a celestial fantasy. Once again, our theology must have a passionate, futuristic zeal, preceding and shaping the technologies and institutions necessary to actualize them.

To shift the sacred from two hundred-odd nation-states to the planet itself does not imply any assault on states. The goal, instead, is radical preservation.

Twenty-first-century theologians will necessarily depart significantly from Enlightenment thought, however. There were good reasons in the eighteenth century to assign the surplus divine aura to the national state; today, our political progress is seriously impaired by this maneuver. That every parochial state possesses a separate sacred purpose results in enormous violence—within and between states—as well as a ruinous competition over the consumption of nature. If we are to turn our “globalization” from a gangster racket into a political society, the divine aura must be assigned to nothing less than the planet itself. The backdrop to all action is the planet; the success of our economy depends on its harmonization with the planet; the moral standards by which our lives are judged come from the planet.

Once again, this immediately requires another, parallel invention: the planetary people. In their state-fixation, liberals have become fond of mocking the possibility of such an amorphous collective. In the process they forget the history of liberalism itself. For such liberal pioneers as Giuseppe Mazzini and Jawaharlal Nehru, nationalism and internationalism were two faces of the same thing—and they could not be separated without great moral loss. The creation of a “national people” from the mutually incomprehensible castes and tribes inhabiting so many nineteenth- and twentieth-century states, moreover, was more far-fetched than the creation of a “planetary people” today. Contemporary cybernetics, after all, allows us to visualize the planetary totality as never before; many people already spend far more time interacting with de-territorialized networks than with national communities.

Increasingly, moreover, the only justifiable perspective is that of this planetary people. The previous era taught us to respect the legitimacy of national democratic majorities; since 1945, however, governments fielded by such majorities have presented by far the greatest danger to world peace. National majorities often vote, also, to dispossess minorities—who have no recourse since the only guarantor of their human rights is the oppressing government itself. No absolute legitimacy, in short, can emerge from national processes. Only the planetary people can produce this legitimacy.

Another significant departure from Enlightenment thought, and indeed from the wider Judeo-Christian tradition: the “planetary people” must also incorporate the perspective of non-human actors. The history of modern state formation is the history, also, of the progressive silencing of non-human voices. We now possess cybernetic resources that can restore those voices to our political conversation, but first we need a theological account of the interconnections between human beings and the other residents of the earth.

Two final notes. First, to shift the sacred from two hundred-odd nation-states to the planet itself does not imply any assault on states. This is not another Puritan project bent on the destruction of everything that is; the goal, instead, is radical preservation. Part of the purpose of unburdening nations of their theological role, in fact, is to allow them the better to flourish. As low-intensity units—like provinces or regions today—they can adapt, fuse, or disassemble without cosmological collapse. In a planetary context, rather than the national, cities and regions can also act more autonomously.

Secondly, theology is dead until it enters culture. The theological innovations of the eighteenth century became generally intuitive because they inspired a cultural explosion. Artists, musicians, and writers dramatized the new arrangement of citizens, states, and God with innumerable paintings, sculptures, novels, and anthems. These works were felt to be a part of an immense moral resurgence, which is why they were consumed with such euphoria. The next theological renewal will also require a parallel renewal of culture.

The nature of God, the purpose of earthly life, the relationship between human beings and nature: these are not foreign questions to theologians. With the decline of theology, however, the dominant states—especially—have lost their ability to monitor their own deep structures. They are seriously unprepared, as a result, to deal with the fallout of liberal decline. Nor do the institutions exist where scholars from different religions and philosophical traditions can debate with and learn from each other—a staple of metropolitan life in, say, Tang China or the Ottoman Empire under Bayezid I. We need to recreate these lost capacities. Without them, all the political resources we have accumulated till now, often with great care and sacrifice, will collapse on their insufficient foundations. Theology is the future.