The Art of Broad Listening

To revitalize democracy in the age of AI, we must pivot from one-way broadcasting to dynamic broad listening. Innovators in Taiwan and Japan are leading the way.

For hope of democratic politics in the age of AI, East Asia is worth a closer look.

While most attention is on the declining cost of AI-generated misinformation and division—all the more so since DeepSeek shook the AI world—the focus in Tokyo and Taipei has turned to the similarly declining cost of AI-facilitated democratic participation.

Let’s start with Tokyo’s gubernatorial election last July. It was won by the incumbent, Koike Yuriko, but all the talk was about the runner-up, Ishimaru Shinji. Ishimaru was not backed by any political party, but he had 300,000 subscribers on YouTube. His success as an outsider, winning over 24 percent of the vote, was covered globally. Social media-fueled populism has finally reached Japan, said the headlines.

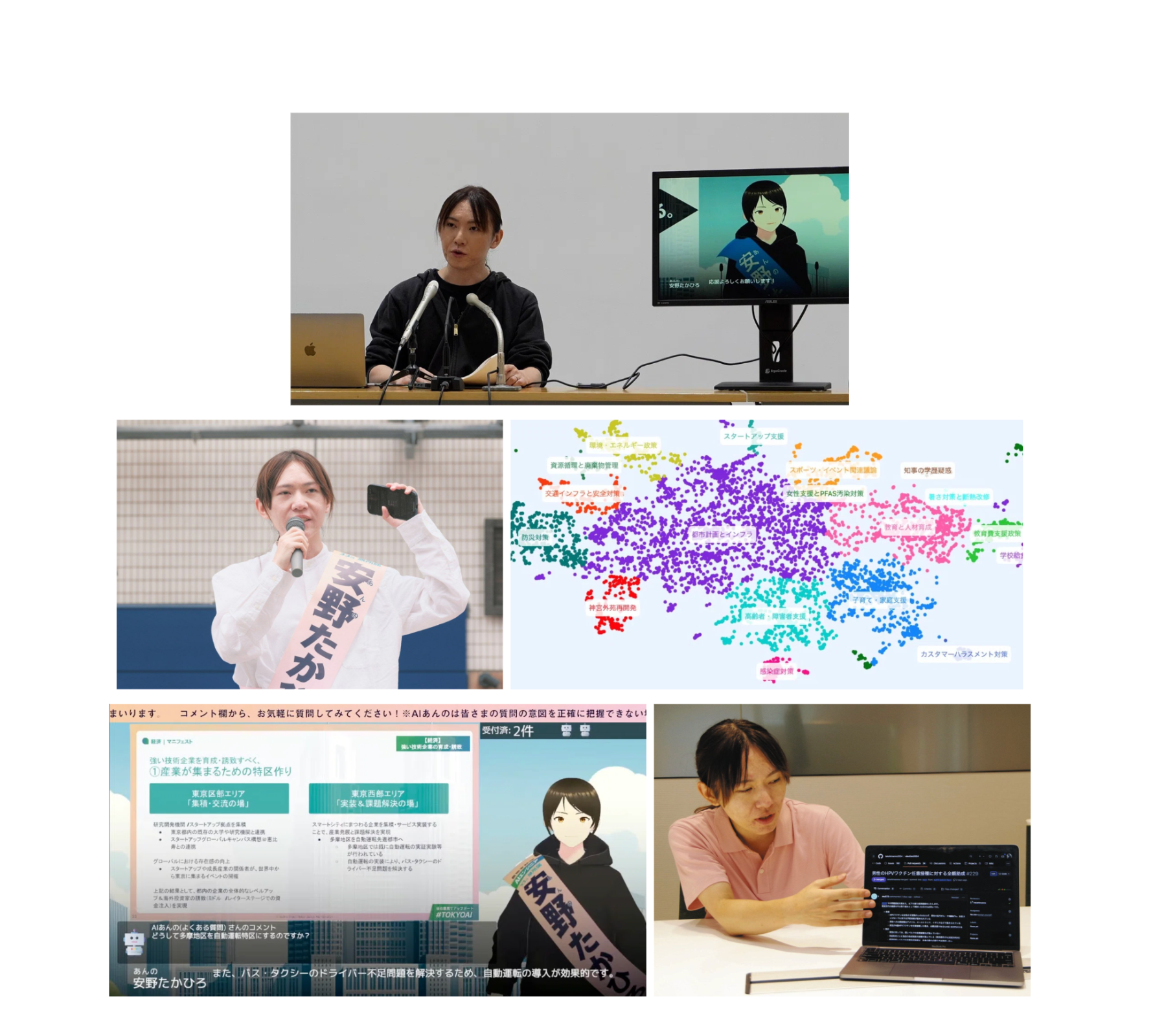

The headlines missed the much more promising story of another successful independent, Takahiro Anno, a 33-year-old AI engineer who placed fifth with 154,000 votes, or 2.3 percent. This was the most in Tokyo’s history for a candidate under 40 years old, and the most for a candidate without any experience as an elected official.

The strategy behind Takahiro’s campaign was the first of its kind: using cheap digital tools to facilitate a better two-way conversation at-scale between the candidate and citizens, or what can be called “broad listening” (the opposite of broadcasting). He credits the concept to the “inspiring” book, ⿻數位 Plurality, written last year by E. Glen Weyl, Audrey Tang, and dozens of other contributors. As it turns out, some of those contributors live in Tokyo, including Nishio Hirokazu, a software engineer and the book’s Japanese translator. They all joined the campaign.

Together they built nothing less than a new state of the art of digital democracy. They visualized Tokyo’s political discourse on social media using Talk to the City, and then used language models to facilitate healthy and productive online discussion about it. The outputs were used to continuously update Takahiro’s policy agenda, which was posted on GitHub, where his supporters collaboratively made hundreds of issues, pull requests, and merged pull requests. Takahiro even used an avatar (an “AI Anno”) to help communicate these updates to citizens. He credits the avatar with answering 8,600 questions over 16 days on a YouTube livestream, far more than Anno-san could have managed himself.

The process was made open-source and free for others to use, but there were some limitations. First, participating in the campaign required familiarity with technical systems like GitHub, which most people did not have. Takahiro was able to attract plenty of support from the kinds of people who naturally want to try out new technology, but that won’t be enough for most political organizers. There is “tech debt” to be paid in order to make similar efforts easier and more cost-effective than conventional methods of mobilization. Second, it was set up more for one-to-one feedback than genuine group deliberation. As Audrey Tang said in conversation with Takahiro, “ChatGPT does not introduce you to new friends, or hold a conversation with 5 people at the same time.”

Tang had these limitations in mind when she led a similar effort last spring with Taiwan’s Ministry of Digital Affairs. Seeking public opinion on various policies that would aim to promote the integrity of information on large platforms, the Ministry assembled nearly 450 individuals—a stratified random sample of some 200,000 citizens, who were contacted via the government’s official “111” SMS code—into virtual rooms of 10.

Except the facilitator in these rooms was an AI system, rather than a paid professional. By most accounts it did an adequate job: encouraging everyone to speak, “de-duplicating” common discussion points, helping make sense of disagreement and where bridges to consensus might be made. And it did so, crucially, at a fraction of the cost of professional facilitation.

In the end, the opinion of this “microcosm of Taiwan” helped shape the proposed Anti-Fraud Act, which the Legislative Yuan later passed into law. (The new law, among other things, mitigates online fraud in Taiwan by holding platforms liable if they serve any ads that use deepfakes and AI to scam users. In response, Meta and Google have invested in infrastructure to verify the integrity of their ads with wide reach on the island.)

Not to be outdone, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government—led by Governor Koike who defeated Takahiro in the election—announced in November that they would work with Takahiro to make broad listening a constant force in Tokyo. They recently completed their first initiative, incorporating the voices of almost 28,000 citizens into an updated “Tokyo 2050” strategy.

Building on the success of broad listening, Takahiro now has plans to make Japan “the world’s most advanced nation in digital democracy by 2030.” Various political parties, in advance of this summer’s elections in the House of Councillors and Tokyo Metropolitan Assembly, appear to be getting on board. And it’s clear why. In a moment of deep uncertainty for Japanese politics, broad listening is pointing the way to a more stable future.

But the same goes for the rest of the world. Weyl and Tang are calling for a new paradigm of “Prosocial Media,” in which our algorithmic feeds start to surface content based on the principles of broad listening. As one example, Puja Ohlhaver, a core contributor to the Plurality book, has proposed extending the Community Notes feature on X into “community posts.”

While Elon Musk imposes his vision of social media and government efficiency on the West, Takahiro, Tang and their many collaborators are quietly showing there is another, better way. It’s time we all listen.